2003 –

I returned to Australia in 2003 with my now four-year-old daughter. This was a very difficult time as we extracted a new version of our little family of three. I will always be grateful for the legndary support of my parents. My art continued through the turbulence, and I threw myself into completing a series of medievally inspired geometrical paintings in preparation for another solo exhibition.

Throughout my journey into fatherhood, through Europe and back, I had become deeply engaged with Buddhist philosophy and meditation. I read extensively and practised consistently. It was a natural progression to begin viewing my Christian-inspired artistic practice through the lens of Buddhist thought.

Buddhist philosophy differs profoundly from Christianity. It doesn’t rest on belief in a god or a heaven. Instead, it offers an eightfold path—a practical, grounded way of being that leads to greater clarity and peace of mind. Nirvana is not a place but a way of existing, achievable here in this life. In many ways, it’s the original self-help course.

My knowledge of Buddhist imagery came largely from Tibetan mandalas (literally, “circles”) and the iconic sculptures of the joyful, plump Buddha. I loved contemplating the contrast between the smiling Buddha and the suffering Christ—joy and agony. That tension fascinated me, and I explored it in earlier paintings.

So it felt like a natural next step to shift from the square to the circle—to explore the possibility of expressing a kind of “Buddhist geometry.”

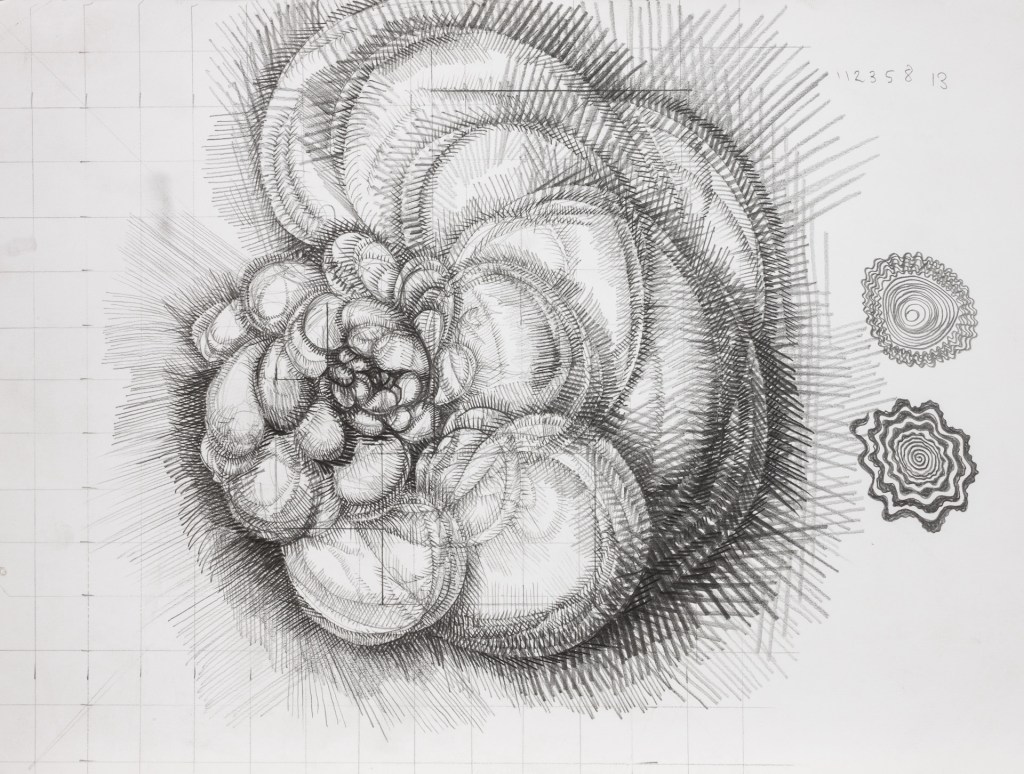

As is often my way when trying something new, I began small. Better to solve the problem on a tiny scale first. I filled sketchbooks with hundreds of forms that grew from the centre outward—organic, rhythmic, like something living. As the work progressed, the circle became less a container and more a suggestion. The forms began to generate their own internal momentum.

My initial thinking was something like: Create a circle using a series of smaller shapes that radiate outward from the centre, suggesting growth—like an organism.

Later, it evolved to: Start with a simple shape (a crescent, for instance), and then continue drawing by connecting that same shape in a rhythmic way, allowing for gradual variations in size and direction—mimicking the gentle persistence of natural growth.

The process became meditative, and the geometry began to feel less like design and more like discovery.