2001 – 2005

I left Sydney just after the 2000 Olympics with my partner and our three-year-old daughter, bound for Milan in search of creative adventure.

I arrived with some confidence as an artist, encouraged by early abstract work. But I soon encountered a different kind of abstraction—the geometry of Medieval Europe.

The first night in Italy exposed cracks in my relationship, which eventually broke down. That emotional upheaval became the backdrop to an incredibly creative and transformative period.

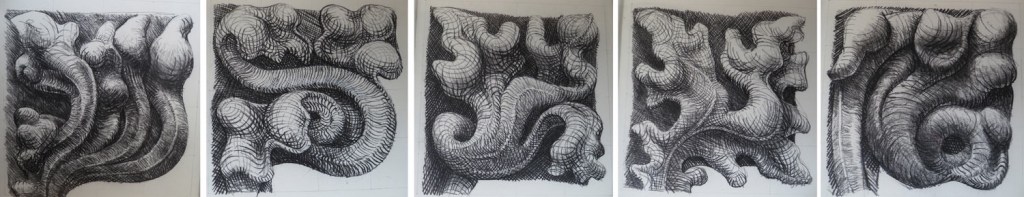

I was immersed in cultural richness: medieval drawings, gothic cathedrals, Italian design, a new language—and full-time parenting in a foreign city.

Life became a mix of surreal and ordinary: church visits, fresh gorgonzola, starting a business for expats, cycling Milan with a toddler and toolbox. Quiet moments in fields, hectic travel across Europe, and a blur of art, life, and learning.

The turning point came in Bourges Cathedral, France.

At art school, the Renaissance was portrayed as Western art’s peak. But I saw greater brilliance in the medieval guilds—merit-based, skilled collectives that built soaring cathedrals, including Bourges. Their work felt more noble, collaborative, and spiritually alive. (Gaudí’s Sagrada Família is a modern example)

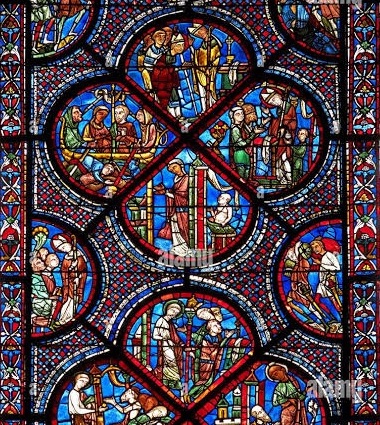

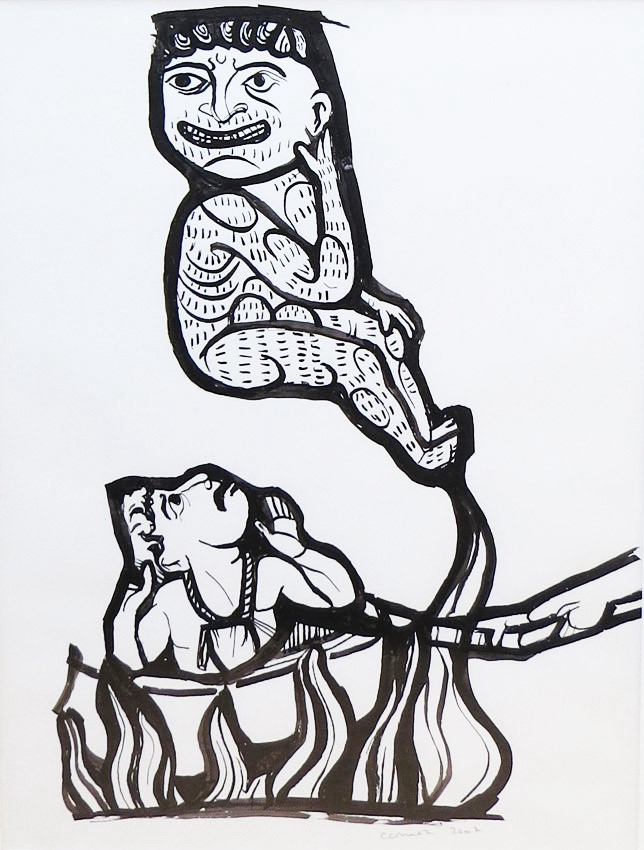

What stunned me most were the stained glass windows—raw, hand-drawn portraits of saints, devils, peasants.

Each window told rich biblical stories, etched lightly on coloured glass and fired through unpredictable techniques. Seven centuries later, the glass still shimmered. Sunlight gave them new life each day.

On my second visit, I spent a week drawing before those windows while my daughter played on a rug nearby. Deep focus was punctuated by toddler chatter—held together in a luminous world of shifting colour, organ music, and ancient stories.

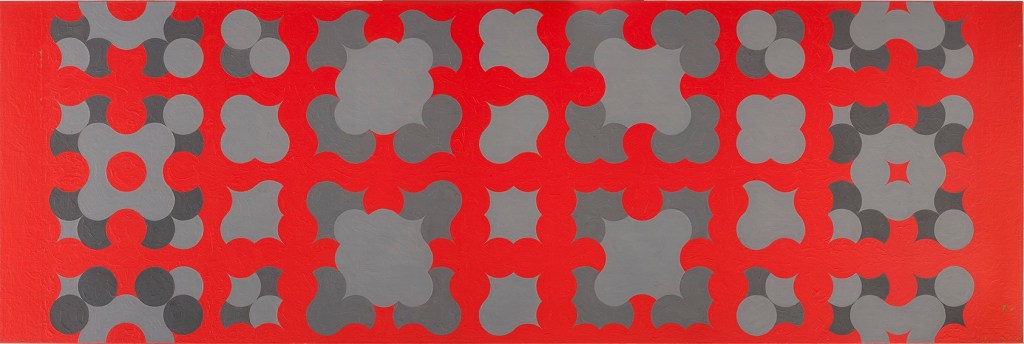

Each window had a dominant hue and a unique internal geometry. Their playful, thoughtful variety within a rigid structure moved me deeply. Gothic music echoed, then silence.

Coming from a culture of mass production, where uniformity is prized, I was struck by the idea that utility and playfulness could co-exist—that variation could be part of a design’s soul.

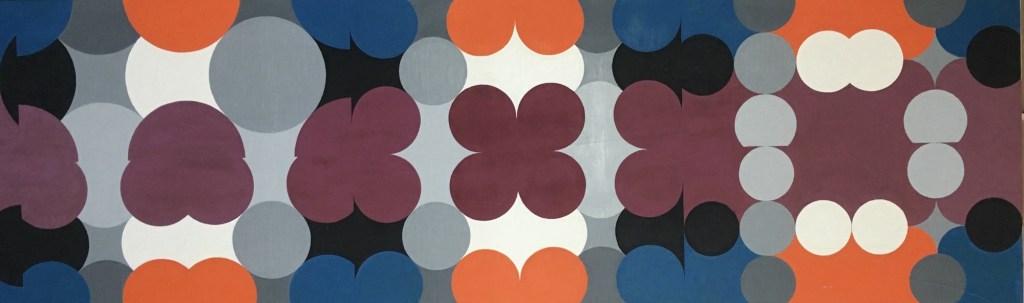

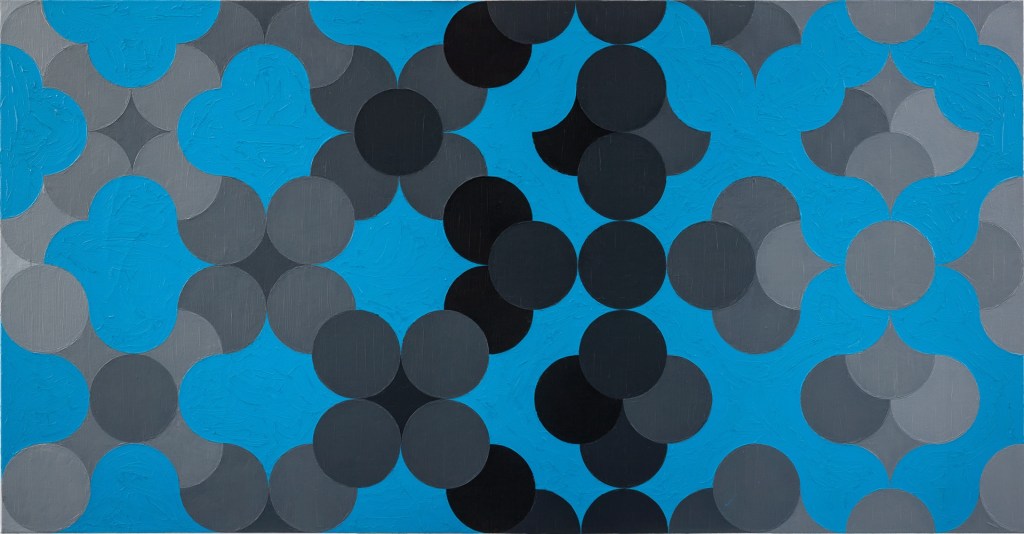

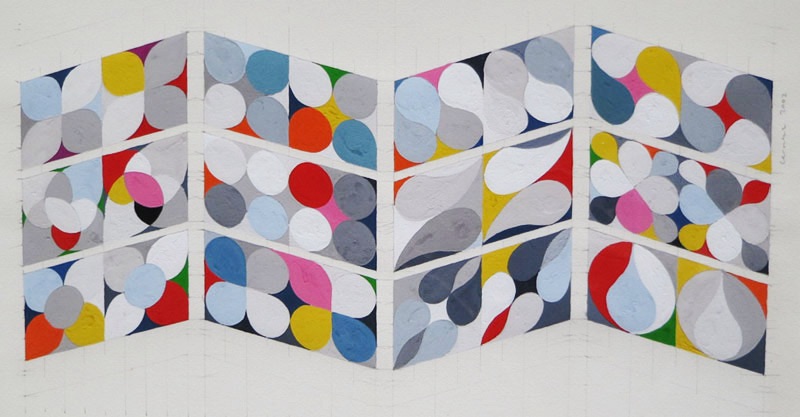

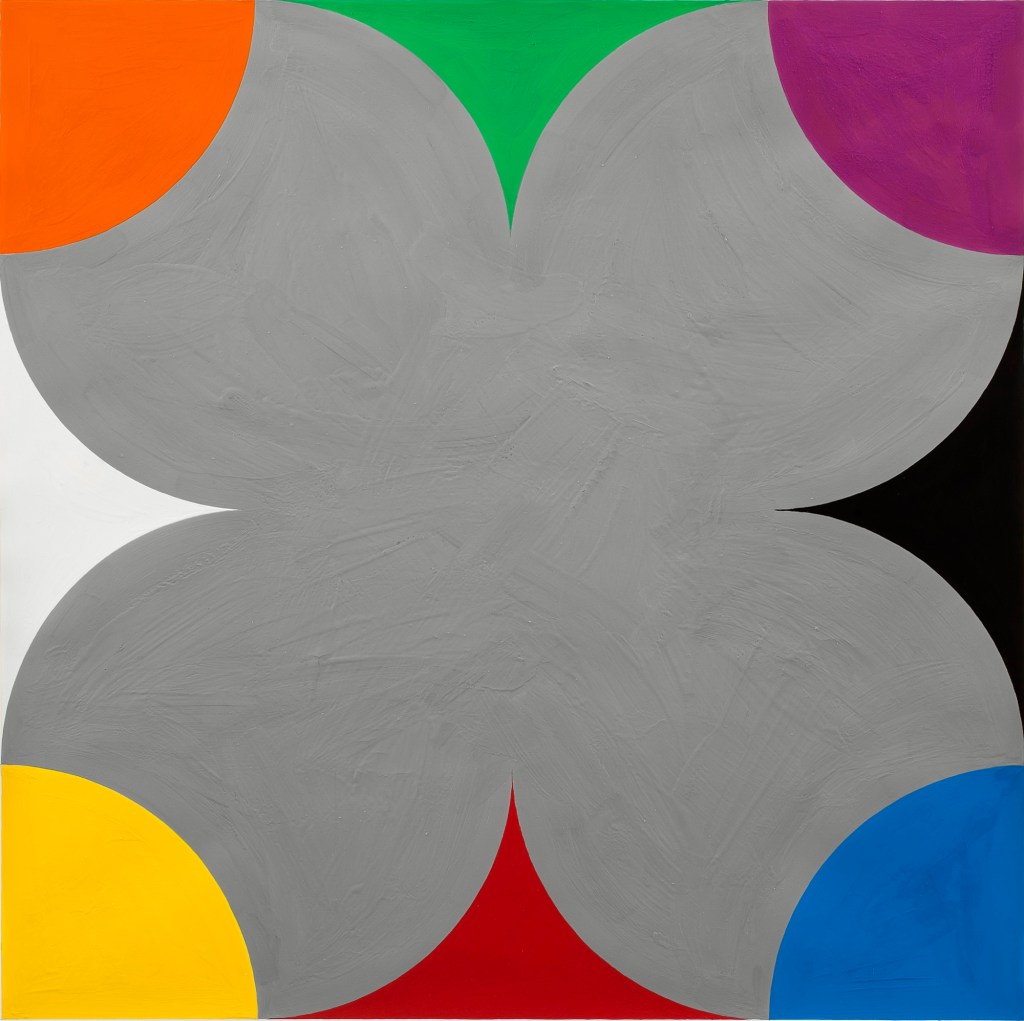

Inspired, I gave myself a challenge: instead of the gothic arch, I’d use the modernist square. My goal was to invent new designs within that constraint.

The challenge –was so nerdy:

Using only arcs of a constant radius, divide a square into nine segments. The divisions must be symmetrical—vertically, horizontally, and diagonally.

I started sketching. Six patterns became twelve, then thirty, then a hundred. Within months, I realised the variations were endless.

This evolving collection of geometric designs became the foundation for a new series—shaped by mathematical rules and my response to the Christian guild geometry surrounding me.

I often return to this series—the simplicity of it makes it a great way to begin a project.